This second article in our Bitcoin Building Blocks series looks at why Bitcoin is ideal for sending and receiving micropayments, offering an alternative to our current global financial system that does little to benefit everyday consumers. We look at the origin of blockchain technology not as a speculative investment, but as electronic, peer-to-peer cash.

What’s wrong with our financial system?

The start of the 2008 white paper outlines the scope of the problem Bitcoin was designed to solve: “commerce on the internet”. Satoshi Nakamoto’s vision is big, encompassing a new system that allows people to send and receive electronic cash without the need for financial institutions in the middle. But are they such a bad thing?

While the system works well enough for most transactions, it still suffers from the inherent weaknesses of the trust-based model.

Satoshi Nakamoto, 2008

The Bitcoin creator identified two problems with the current online payments system:

- Using traditional infrastructure, even small payments can be reversed, whether a customer received their goods or not. This means merchants must request lots of information to verify customer details, and banks need to insure against the risk mediation, increasing the cost of transactions.

- A central mint must double-check every transaction to make sure an electronic ‘coin’—the individual value being transferred—isn’t duplicated or spent twice. This means existing payments systems are centrally controlled by single entity and exposed to man-in-the-middle attacks.

The cost of inefficiency

Both require trust. Since merchants and banks need to either trust customers or collect personally identifiable information, transfers tend to be expensive. Conversely, customers do not trust that private companies have their best interests at heart, both in terms of GDPR and in terms of making profit.

Banks and payment providers do offer an important service, allowing us to send money anywhere in the world, but few could argue that the current system is secure or efficient. Just have a look at your options when it comes to international transfers.

Estimated cost of sending £100 internationally :

HSBC: £10

PayPal: £2.99

Wise: £1

Given that we can simply hand physical cash to another person, the idea that digital payments would have hefty fees of up to 10% seems absurd. Yes, commerce on the internet does have a cost which needs to be covered to allow a transaction, but all too often the payment infrastructure used does not match the requirements for a modern-day internet, or the internet of value. Exchanging online should be much less complicated than it seems—requiring only minimal amounts of data.

What is needed is an electronic payment system … allowing any two willing parties to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party.

Satoshi Nakamoto, 2008

The solution: Electronic cash

Bitcoin is a peer-to-peer version of electronic cash. Lightweight software can run on an electronic device such as your smartphone, allowing you to send transactions worldwide to anyone with a digital address—instantly. When people exchange value, for example by buying a coffee from the local café, they are passing an electronic coin—bitcoin—between them, the amount of which can vary.

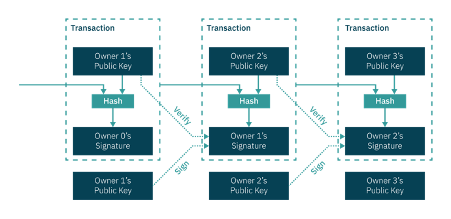

To ensure security, and build trust between two parties directly, that electronic coin is just a chain of digital signatures with the history of every transaction included within it. Senders typically use their private keys, which may be accessed using a digital wallet application, to authorise the transfer. And to prevent data from unnecessarily growing in size, transactions are ‘hashed’, cryptographically converted into a fixed-length string of letters and numbers. The system protects personal information and the privacy of honest users, while small payments are economically infeasible to reverse, protecting merchants from fraud.

Transactions on the blockchain

After a transaction has been handed from one user to another, reference information about your transfer is added to the distributed blockchain database by nodes, known as ‘miners’, that record and verify the data (contrary to popular believe, payments don’t go through nodes). As we saw in the first article in our series, the easiest way to think of transactions is like cells in an Excel file, arranged into blocks—worksheets—that form an ongoing chain.

An example of a private key:

E9873D79C6D87DC0FB6A5778633389F4453213303DA61F20BD67FC233AA33262

Because users themselves can verify their own transactions, using what is called simplified payment verification (SPV), and query the nodes to confirm the status of a transaction, and that it has not already been spent (removing the ‘double-spending problem’), there is no need for a central mint or private company to verify transactions or issue new coins. Your coffee shop can see a payment is legitimate and be confident enough to hand the customer their coffee by simply checking the transparent, public record and seeing if most nodes say it is.

Bitcoin and micropayments

The intended application of Bitcoin is different from the common understanding today. Many people use the term interchangeably with ‘cryptocurrency’—which we see as a misnomer associated with a risky asset where holders see the value going up over time as a speculative investment. We believe the system must mainly be useful as a low-cost, secure peer-to-peer payments system, as is outlined in the white paper. Bitcoin is not a currency, although tokenisation methods would allow for the creation of a national ‘central bank digital currency’ on top of Bitcoin.

Micropayments are possible because we remove the need for third parties like VISA, SWIFT or banks, and therefore reduce the fees involved, and the minimum amount possible to send is miniscule, just one hundred millionth of a single bitcoin. BitcoinSV, the blockchain network we help maintain, potentially allows users to exchange value for fees as low as £0.001 or even less. It is a model that puts everyday people, individuals first, enabling them to engage in global trade.

Everyday use cases

Small payments are meant to be built into the very internet we use every day. You’re probably used to seeing a ‘404 file not found’ error when visiting a web page that doesn’t exist, but have you heard of the ‘402 payment required’ status code? It was a relatively unused feature to be integrated with a future online micropayments system that, until Bitcoin, hadn’t yet been built.

Any commercial entity that makes payments, receives funds, or settles accounts internally has a use for Bitcoin. Uptake is often hindered by a lack of proper due diligence around the choice of blockchain, or robust technical onboarding to ensure interoperability. Some possible ways Bitcoin’s electronic cash system can revolutionise commerce:

- Consumers receive a fraction of a cent for seeing a brand’s social media advert

- Content creators receive a fraction of a cent for every ‘like’ or comment on a post

- Viewers pay only for the first minute of a Netflix video if they stopped, not the full movie

- Businesses set lower minimum prices for goods to stay competitive and still be profitable

Scalability is crucial

Whether or not micropayments are possible depends on a system’s efficiency and scalability; and nChain’s work to maintain the Bitcoin SV Node software—for node operators of the BSV blockchain network—aims to ensure exactly that. Besides the infrastructure we develop and a number of patents we’ve filed around micropayments, you can read more about our Digital Cash product here. We believe micropayments can be transformative for people and businesses alike, with benefits from financial inclusion to lower operational overheads.